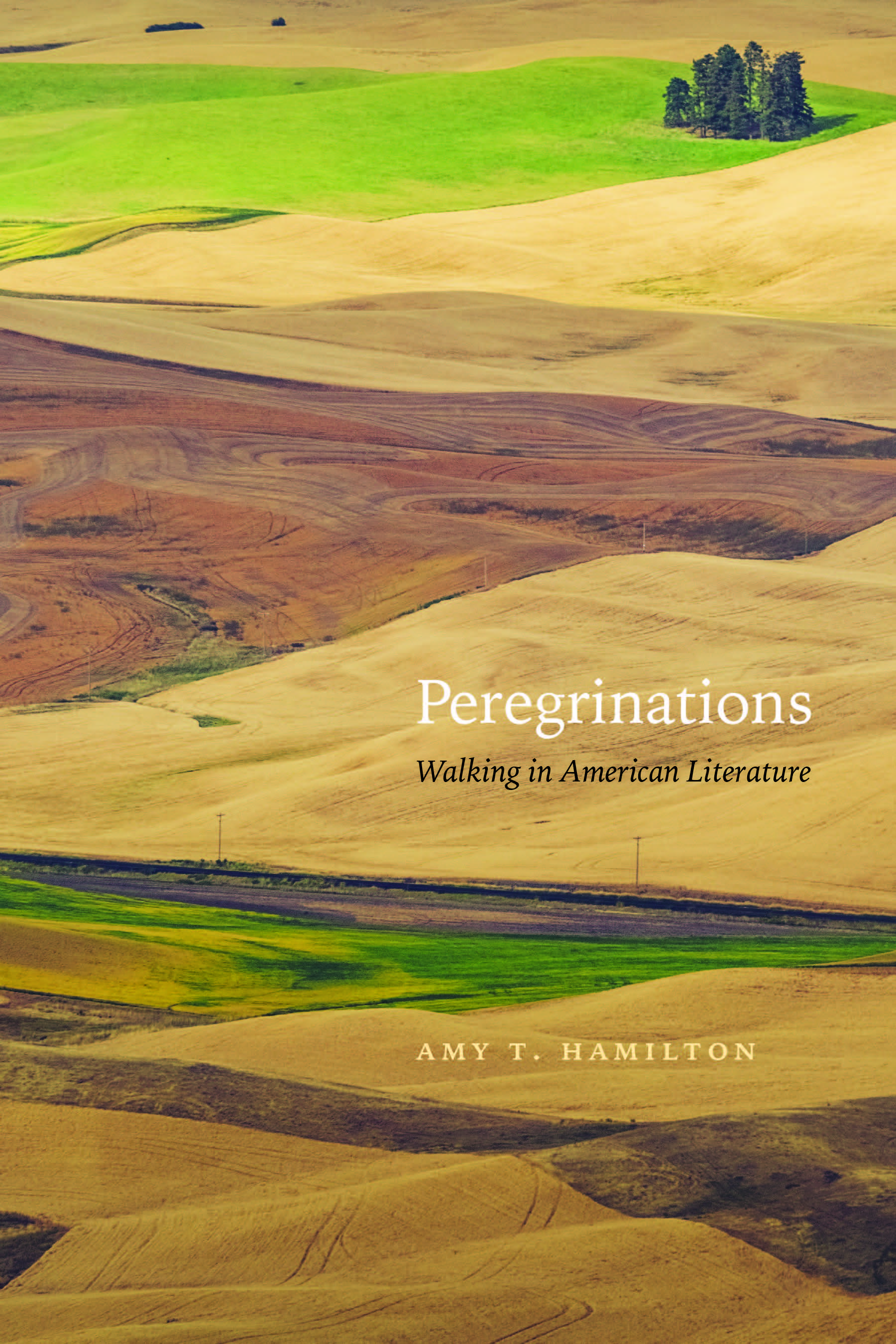

Amy Hamilton

University of Nevada Press, 2018

Humans have crisscrossed North America since long before the collision of the Old World and the New; some of the continent’s inhabitants predate Columbus by tens of thousands of years. The Columbian exchange that came after is marked by hundreds of intertwining cultures, every one of which walked the land we walk today. Unremarkably, many of them wrote about it. But what is remarkable is that only a slim selection of their stories are still shared or examined today.

In her book, Peregrinations: Walking in American Literature, Amy Hamilton writes: “Indigenous walkers were joined by French trappers, Spanish conquistadores, Puritan settlers, western pioneers, Chinese railroad workers, African American slaves, and scores of others moving across the American land. Their footsteps multiplied and broadened the paths pressed into the earth [and], as the kinds of walking and the footsteps themselves increased, the movement of Euroamerican settler-colonists quickly pushed other walkers off the path of American literature and history. Walking in America became associated primarily with white men.”

Stepping into the wilderness has become an archetypal coming-of-age experience for young American men I won’t pretend I didn’t embody when I thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail as a 22-year-old college graduate. The majority of other aspiring thru hikers were similarly aged, similarly gendered, similarly complexioned individuals intent on the same cliché, over-romanticized, soul-searching rite of passage: testing their mettle against the American “frontier.”

Indeed, the outdoor industry as a whole has long struggled with inclusivity and accessibility, catering to the demographic with the right amount of privilege (education, time, money). This phenomenon is deeply rooted in historical and societal inequalities, but, despite how exclusive the American “wild” has become, there is still a vast sample of literature from “unconventional” voices—a fallacious term, privileging the aforementioned white-dominated perspective as “usual” or “normal”—that tell of intimate relationships with the land.

As homogenized as the crowd is on the Appalachian Trail, it’s hard—while on it—to miss the true identity of the terrain it traverses. The worn, aged hills of the Appalachian Mountains are maybe the best exemplar of land across time, the deepest underpinnings of life on this continent. Humans—not just white American men—have lived on and across the same land for millennia, and it’s a selection of this variety of stories Hamilton examines in her book.

Far from a crusade against whiteness and manliness, whatever those things are, Hamilton’s work brings to light the universality of walking as a deeply human experience and elevates underrepresented narratives to the level of the John-Smith-Davy-Crockett-Lewis-and-Clark American love affair. In an age of rocket ships, bullet trains, and nuclear submarines, it’s worth remembering that walking is the foundation of all our advancements. Everything we are now as a species was born of the most rudimentary bipedal locomotion. Crossing country with this deliberate, efficient, upright cadence is the fundament of the human collective, and that is even more relevant now that the “long history of imagining the origin story of America as the struggle of rugged Euroamerican men claiming and taming the American land” has falsely simplified both the sticky, convoluted birth of the United States and the diverse history of people crossing land with their own two feet.

Peregrinations, in its own words, “illustrate[s] that walking in American literature suggests a rich range of cultural histories and worldviews as well as consistently foregrounding attention to the material presence and agency of the American Land itself.” If we stop conflating America and the land upon which it was founded—land that was here eons before the nation was founded—we can appreciate abundant more interactions with the landscape. Walking is not just the tired tropes of Daniel Boone and Manifest Destiny, but the way by which all people who have set foot on this continent have explored, suffered, worshipped, and died or survived.

This is to say that there is more to walking than practical travel, and, in terms of landscape, not all walking is created equal. Walking is an interaction between a human and the terrain he or she crosses. How the geography affects one’s stride and the pain and fatigue it incites in the human body gives agency to the land itself. The labor—and understanding—the country demands animates the topography of the continent into an autonomous character in any ambulatory narrative. And of those, Hamilton runs the gamut. From the religious, feminist, cultural, historical themes of Indian captivity narratives to the timely literature of southern border crossings, Hamilton thoroughly examines the movement of the human body across North America, producing poignant critical theory that considers the work of Sarah Wakefield, Mary Austin, Luis Alberto, and Louise Erdrich, among others.

What emerges from these analyses is a systematic look at the records—both the content and the craft—of walkers who came before us. For me specifically, what emerged was not disenfranchisement with my own long walks or disgust in the prevalence of the Manic ’Merican Macho Man in today’s backcountry, but instead a sincere and sight-shifting appreciation for the breadth of people who have shared in the arduous, humbling, magnificent errand of crossing this certain body of land under their own power. Anyone who has walked—or holds the ambition to walk—through this country’s deserts, mountains, forests, or vales owes it to themselves to read this book. It is a chronological critical catalogue of the stories you never hear, attesting that the act, portrayal, and meaning of walking are simultaneously universal and varied.

For the Puritans and their Native captors, the American Indians and their infantry escorts, and the parched immigrants and the agents tracking them over the border, walking was and is both sovereignty and enslavement. Hamilton shows us that we are only the followers of the followers of the followers, and that the more we appreciate the ones who followed before us, the more enriching a walk in the woods will be.

Reviewer Bio: Brendan Curtin is a triple-crown backpacker who grew up in the snowbelt of Ohio and sheep pastures of New York. A 2013 graduate of Hiram College, he joined the MFA in Creative Writing and Environment program at Iowa State University in 2017. He loves bears, owls, and the smell of old sleeping bags. His work is published in Trail Runner magazine and Appalachia.