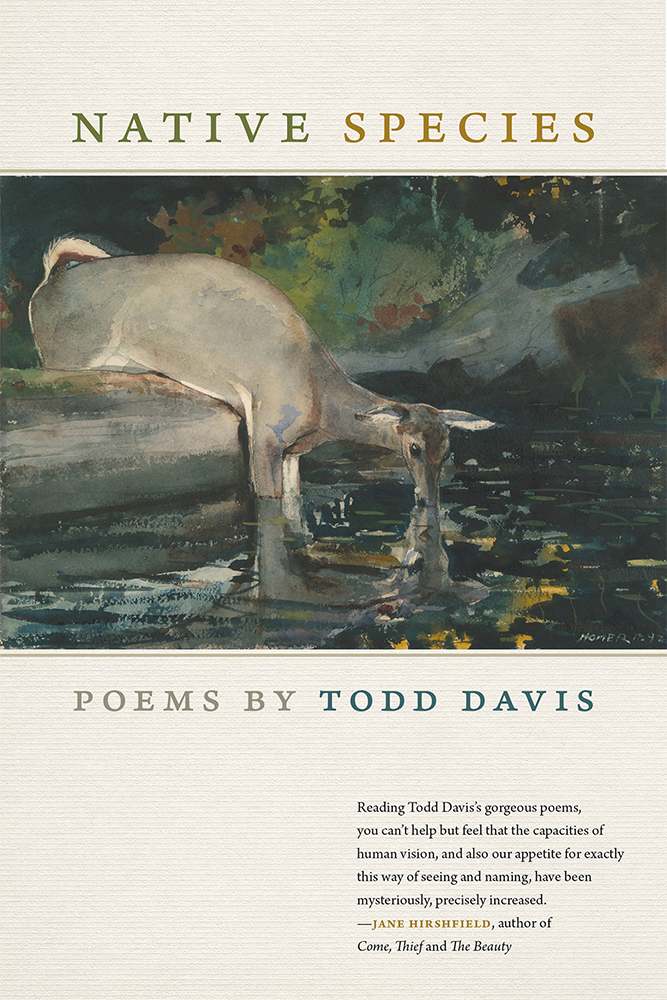

Todd Davis

Michigan State University Press, 2019

As a farmer, I work in seasons and annual cycles of life and death. I appreciate how the bursting new growth of spring eventually devolves into the wet, dank of winter. I pay attention, generally, but when things get hectic I neglect the subtle offerings of this land. Seed to supper, milk to cheese, bedding to beautiful, brown compost. I often turn to discerning poets to remind me of the importance of these sacred, routine transformations.

Todd Davis is one such poet. As an experienced hunter and fisherman, mortality (both animal and human) is on his mind. “We’re always at the mercy of the world,” he tells us in Native Species. In his sixth, full-length collection of poetry, Davis oscillates between worlds and voices, the seen and unseen, with deep respect for his poetic, wild, and familial teachers.

Davis doesn’t let us sit long while we read his poems. Beauty and destruction are often just a breath apart. I savor his images of “elk tramping raspberry / canes” or ravens that “decorate a white-oak snag.” I clench thinking about the floating corpse of a drowned gray fox or the bear destroying a friend’s beehive. The world becomes tangible, tactile, and sometimes terrifying in the deep terrain of his verse.

But redemption, too, is offered candidly. In the poem “Returning to Earth” Davis writes, “I want our children’s hands / to hold the river, to watch it spill / through their fingers, back to a source / older than our names / for God.” To truly love a place is to become that place. To become animal and plant. I was particularly struck by the title poem which describes Davis’ slant on transfiguration; man becomes hallowed prey and stamps “his hoof in dark / soil.”

Like his previous books, such as Winterkill or In the Kingdom of the Ditch, each poem in this collection amplifies Davis’ obligation to relationship and deep, ecological empathy. Yet, several epistolary poems are rooted in grief and alienation. In “Notes on the Anniversary of the Death of Galway Kinnell” Davis laments, “We stick to the earth, / whether something in us / departs or not.” In “Dead Letter to James Wright” Davis quietly confesses, “I am still not sure / what species I am.” Reverence, versus resolution, gently carries the reader across the poems.

When I put this book down I see my day a little differently. I yearn to go back outside, hungry for the exultations of a flittering leaf or eagle call. Todd Davis helps me not take my simple life for granted. He also challenges me to stay aware and unafraid of what may come and, more importantly, what may eventually pass.

Reviewer Bio: Jessica Gigot is a poet, farmer, teacher, and musician. Her small farm, Harmony Fields, in Bow, WA, makes artisan sheep cheese and grows organic herbs. Her first book of poems, Flood Patterns, was published by Antrim House Books in 2015 and her writing appears in several national and regional journals, including Orion, About Place, The Hopper, and Poetry Northwest.