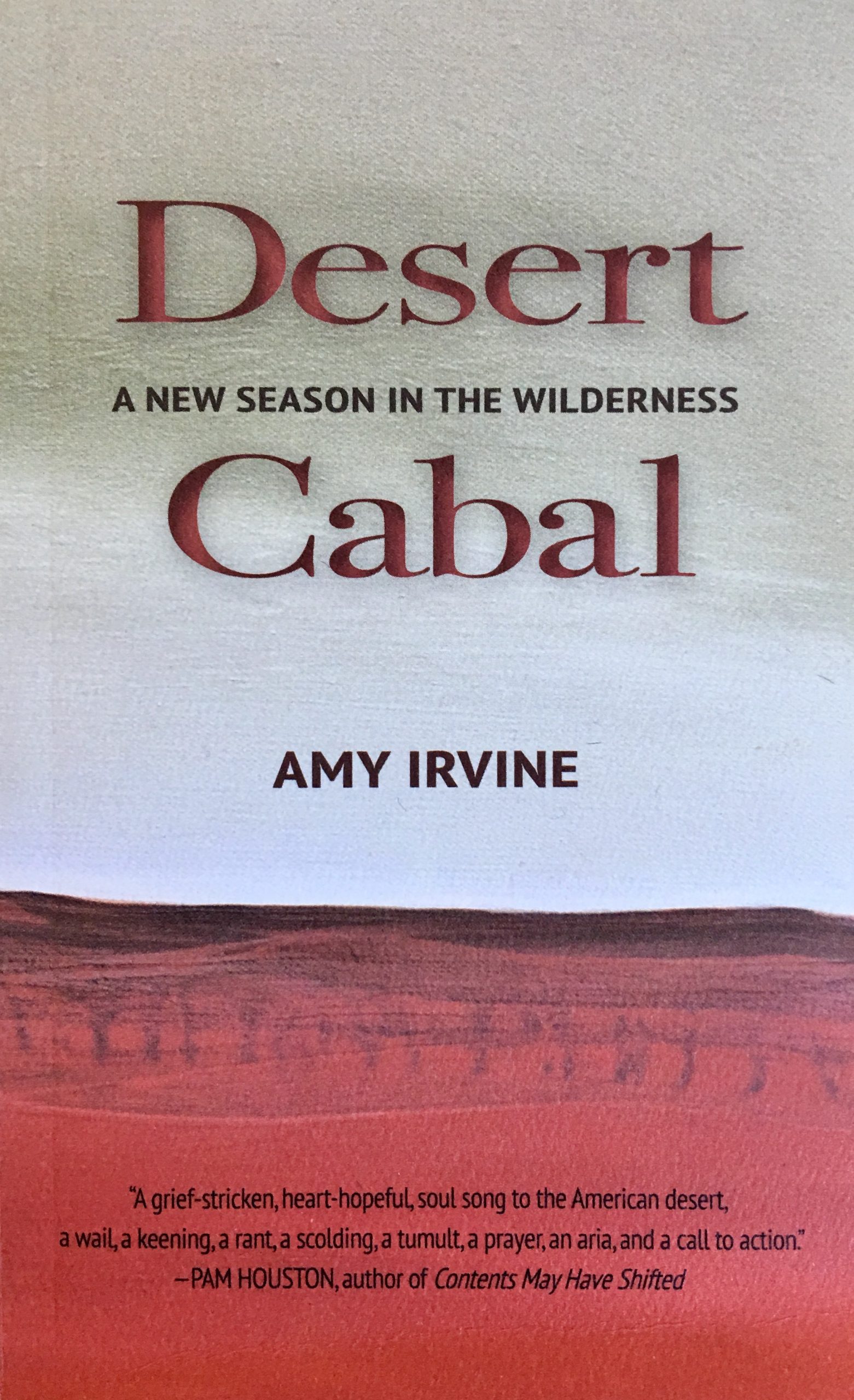

Amy Irvine

Torrey House Press, 2018

It’s been 51 years since Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness was published (“released from its cage and turned loose upon the unsuspecting public,” as it’s said) and 30 since the book’s author, Edward Abbey, died and was buried in the Arizona desert.

Cactus Ed’s final resting place is a mystery to all but a few people, but one of those secret keepers is Amy Irvine, a writer who runs with some of Abbey’s old crowd and who paid the late desert rat a visit on his classic’s golden anniversary.

The rendezvous is recorded in Irvine’s new book, Desert Cabal: A New Season in the Wilderness.

Like other readers of Desert Solitaire, The Monkey Wrench Gang, Down the River, Beyond the Wall, Hayduke Lives!, The Journey Home, and Fire on the Mountain (full disclosure: I’m a fan), I’ve entertained delusions of tracking down the old jackrabbit myself. The most recent fantasization occurred in 2017 when I caught wind of the Mount Washington Cog Railway’s ambition to build a hotel on its Skyline Switch easement, deep inside the alpine zone of its namesake mountain. I imagined holding a séance in the desert—sprinkling mortar from the Glen Canyon Dam on Abbey’s grave, painting the outline of Delicate Arch in the dust with warm Schlitz—until his spirit rose from the rotted sleeping bag to converse by juniper firelight.

But, then, far from haunting Wayne Presby (Mount Washington Railway Co. Owner and Principal of White Mountain Biodiesel, LLC) for all of eternity, he’d probably say us Bean-booted, yacht-clubbing East Coasters were getting what we deserved. He’d say the built-up summit with its auto road, parking lot, gift shop, museum, telephone and radio transmitters, visitor center, and chili-dog-dishing food court was already a lost cause.

I wouldn’t say he was wrong. But I’d remind him he lost Glen Canyon once upon a time and still thought that was worth saving, even after the concrete had set. Maybe now this is just me pulling up an imaginary seat at the table Irvine laid for her and Abbey like an elaborate reenactment of Clint Eastwood’s gimmick during the 2012 Republican National Convention.

But, no, that’s unfair.

Because what goes on in the pages of Desert Cabal is not an empty chair debate. Irvine grills Abbey (who never does rise from the grave), which may not seem like a sporting thing to do to a tired old man, but she isn’t unkind. And she doesn’t fabricate his answers. She is an Abbeyist herself, hopelessly in love with the same deserts as him and just as cutting and heartbreaking with her prose. She isn’t lambasting Abbey for his biases and shortcomings (of which there are many); she is grumpily, lovingly, dragging the old bastard—whom it’s clear she adores—towards contemporary inclusivity.

In brief chapters, Irvine squares off with Solitaire, not to flaunt Abbey’s fallibility or diminish her own, or even to carve out a piece of the desert for herself, but to overlay his story with hers and demonstrate that other people can occupy the same prickly, dusty, hard-edged world so often decreed to be “Abbey’s Country.”

She teaches us that there is something deeper than monkeywrenching, that what matters most is not the act of blowing up the dam, but the motivation behind that act. Fidelity. And fidelity to the land not because of the independence it gives an already privileged man to shrug off bothersome rules and authority, but because of the deep, indomitable freedom it offers those oppressed by the status quo.

Abbey brought the desert and the peril it faces into the American consciousness, inspiring leagues of advocates to defend that sacred southern slickrock. But that slickrock—and all the other open space in this world—is even more imperiled now and it’s going to take more to save it than tall, white, middle-class men (it’s okay, Ed, I’m one too) doubling down on their ownership at the exclusion of everyone else.

I agree with a lot of what Abbey says in Desert Solitaire. That “you can’t see anything from a car,” for example. That “you’ve got to get out of the goddamned contraption and walk, better yet crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbrush and cactus. When traces of blood begin to mark your trail you’ll see something, maybe.”

But Irvine adds to the conversation by sharing experiences that mirror Abbey’s and carry a healthy dose of compassion to boot. She simultaneously demonstrates her worthiness of a desert moniker (Mesquite Amy?) and challenges this parched land’s St. Peter who still presides over the gates of the southern wild from the depths of his grave.

In Irvine’s writing I find everything I love about Abbey’s, plus a little more. Because the bedrock of the desert is still the same, but the voices echoing out of its canyons are changing and that is good. Solitude is important, but solidarity is even more. Whether we’re “looking straight down an overhanging cliff to a rubble pile of broken rocks eighty feet below” or “knee-deep and flailing in quicksand” or up to our chin in a torrent of snowmelt, Irvine reminds us it’s never just the tale of a single person. As she retells it, it’s a much bigger story that encompasses us all:

“It is only truly ours after we have gotten out of the car and wandered far enough off the trail to get lost and use up our last drop of water. Only after we’ve been out enough times—to draw blood, fry skin, write eulogies, pull stakes, see ghosts, and duct tape a flapping sole—should we feel in possession of them. But those of us who have done our time out there know this is the mirage, the trick of light on water that is actually scoured sand. It’s the rough country, after all, that’s in possession of us and not the other way around.”

Book Review Bio: Brendan Curtin is a triple-crown backpacker who grew up in the snowbelt of Ohio and sheep pastures of New York. A 2013 graduate of Hiram College, he joined the MFA in Creative Writing and Environment program at Iowa State University in 2017. He loves bears, owls, and the smell of old sleeping bags. His work is forthcoming in Appalachia.