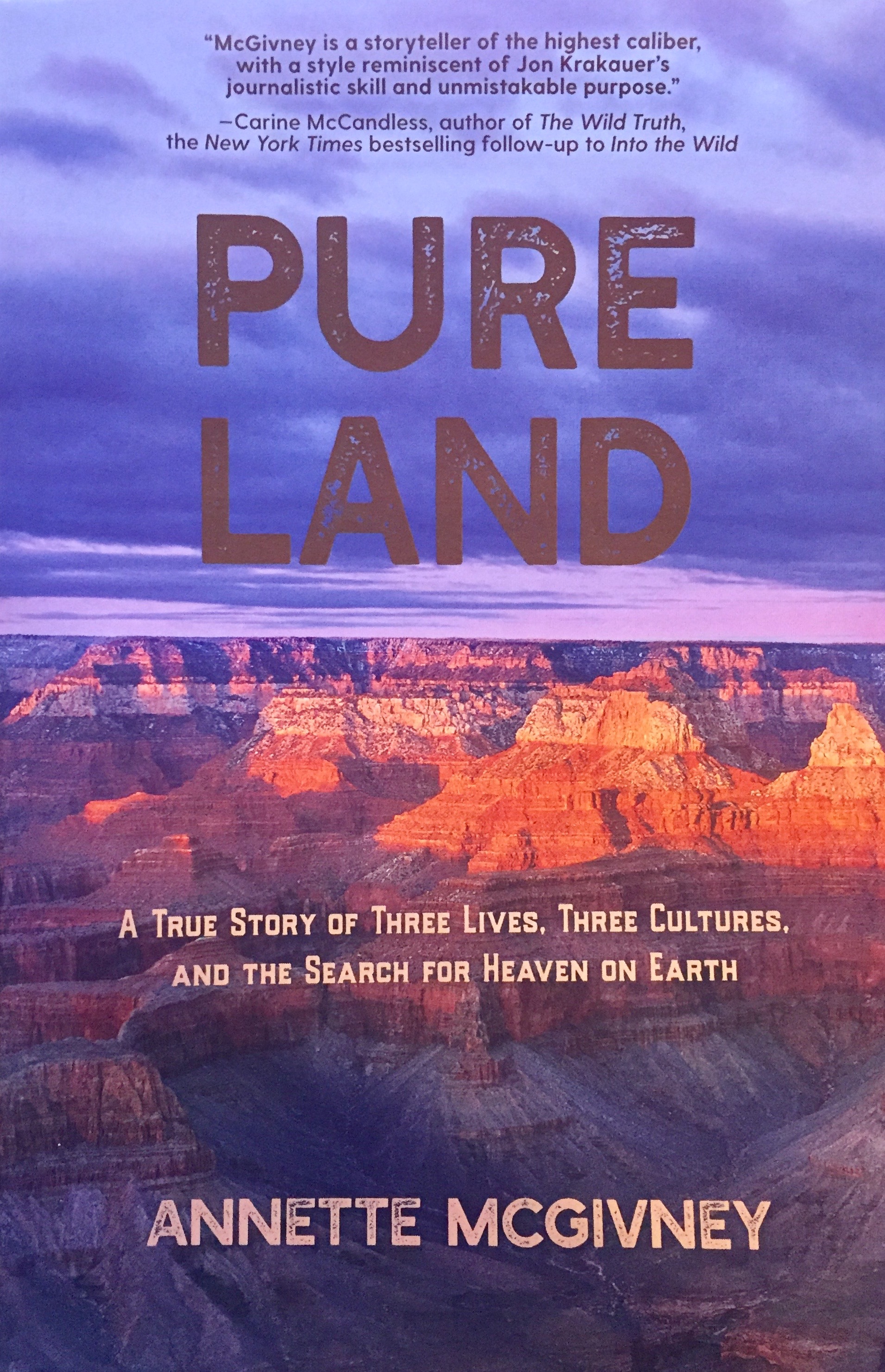

Annette McGivney

Aquarius 2017

On May 8, 2006, a young Japanese citizen named Tomomi Hanamure vanished while hiking in the Grand Canyon. Her body was discovered four days later, half-submerged in Havasu Creek on the Havasupai Indian Reservation. She had been stabbed 29 times.

There is no mystery involved in these details anymore. Shortly after Hanamure’s body was recovered, Randy Wescogame, a Havasupai man with a history of assault, theft, and substance abuse, admitted to committing the murder. He is currently serving life in prison for the crime.

What is left to be investigated are the circumstances that led to this fatal crossing of paths. And that is the undertaking of Annette McGivney—longtime Southwest Editor for Backpacker magazine—in her book, Pure Land.

With exclusive access to Hanamure’s family, friends, and personal journal, the author constructs a no-stone-unturned account of one of the most-gruesome crimes this country’s wild places have ever seen. As expected from such a prolific journalist, the book is meticulous and thorough.

McGivney descends into the Grand Canyon to explore the lives of victim and criminal and the events that brought them together. Instead, she finds herself solving a much larger puzzle and becoming entangled in the mess herself. The result is a complex analysis of the personal and the expansive.

The roots of the murder are traced to the early 1800s and the U.S. government’s abuse of Native Americans. Swindled out of their winter hunting grounds and consigned to a miniscule reservation at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, the Havasupai were quarantined from their own traditions as well as the new Anglo world. The result is a community ill off in health, finances, and education. A community that collides with the America-fanatic Japanese tourist who wanders into its midst.

Hanamure is enamored with the breadth of America, scraping together funds from her jobs at factories in Yokohama to crisscross the States in a rental car, seeking out national parks and unknown corners of the landscape alike. She takes particular interest in the culture of the Navajo and Lakota Indians, chasing their dying heritage across the plains and canyonlands. It is in her hunt for these ghosts that she is killed by the unjust ugliness that has begun to replace them.

But for all the issues this situation might have, McGivney reveals that she has some of her own. While this is hinted at in a tease of a prologue, the eccentricities of a neurotic, physically unwell mother and crimes of a violent, doctor-savior father soon become evident. It’s unquestionable that McGivney sees herself in Hanamure—two determined, free-spirited women searching for their identity in the North American wilderness—but the shock is that she sees herself in Wescogame as well.

The overlap is not in violence, but in abuse and the failures of parenting; sympathy. The difference is in McGivney’s privilege and ability to seek sanctuary in the woods around her home: “From the first time I went hiking alone in the Big Thicket of East Texas at age eight to my first trip to the bottom of Grand Canyon at age 30, I felt a profound and never-ceasing compassion that emanated from the natural world. With that compassion also came a sense of safety and comfort that was not available to me inside my parents’ house or at schools where the teachers didn’t ask about my bruises.”

McGivney exposes the fallacy that is America, both by illustrating the decline of once-prosperous Native American nations and by exposing the ugly underbelly of her own upper-middleclass childhood. Placing Hanamure in the mix makes Pure Land not only a story of the murder of America, but also of those who come to find it. A story of human society and its fundamental failures. A story of abuse and suffering and injustice. And also a story of hope.

While America has a past as troubled and dysfunctional as the families that inhabit it, what McGivney is careful to point out is the opportunity for healing, redemption, and repentance. Of all the characters in Pure Land who are mistreated, not one of them succumbs to ruin.

What’s more, she emphasizes the scope of the outdoors and the inconsequence of mankind against its power and origin. In one of the most remarkable sections of the book, a once-in-a-millennium storm floods the Grand Canyon just weeks after Wesscogame is convicted, razing much of the Havasupai reservation and Fifty Foot Falls where Hanamure was murdered. The scene reiterates the point made elsewhere in the book: that the wilderness heals all wounds.

Or, maybe more accurately, that wounds are nothing to the wilderness. With its eons of memory and the ease with which it dismisses our human endeavors, nature absorbs all hurt. It is from the wilderness we were born, after all, and it is to the wilderness we will return. Hopefully, and to those more enlightened, long before the life leaves our bodies.

Reviewer Bio: Brendan Curtin is a triple-crown backpacker who grew up in the snowbelt of Ohio and sheep pastures of New York. A 2013 graduate of Hiram College, he joined the MFA in Creative Writing and Environment program at Iowa State University in 2017. He loves bears, owls, and the smell of old sleeping bags. His work is forthcoming in Appalachia.