Lungs

They deepen the blood, my grandmother said.

Whatever the blood demanded

was done that time. She was bled like a baked apple

and buried in half-mourning

and brought back from the dead.

I’m sorry, I said to her on the phone.

She said there were white masks

and white gloves and humming beds.

The shit was in the lungs too long, she said.

It was like chicken in milk and black truffles.

Central Ave and Florence

The largest dog I ever saw

lay on the sidewalk: a pit bull

mixed with mastiff, maybe all mastiff.

I circled the block and parked,

but didn’t step out.

I didn’t roll the window down.

I wanted to make sure

because I had almost missed her.

The gray bulk on the gray sidewalk

lost in the colors of the weeds

in the empty lot behind her.

She had been laid out on her side,

her forelegs forward

and her front paws crossed,

mouth closed,

the tip of her tongue pleated,

not quite touching the ground.

Her teats sucked long

and the tips clotted black

and everywhere but the belly

dappled with scars, from the muzzle

to the blunt crease above the eyes

and then all the way down the back.

My god, she was enormous.

More shark than dog.

More lion than anything else.

She had been put down

almost gently on her side,

her paws crossed and banded,

cut-up with wire.

She had been taken out

and left there

like a broken water heater.

But what do you do with a dog like that,

with those scars anyway?

And how many men did it take,

to carry her as far as she was carried?

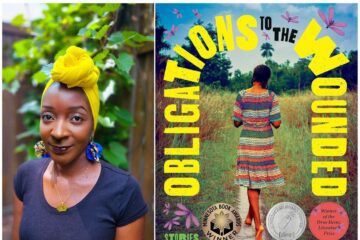

Author Note

When I wrote “Central Ave and Florence,” I was reading a collection of essays by Stephen Dunn (Walking Light). In one essay, Dunn discusses the importance of a narrator’s “complicity” when attempting to register outrage or complaint. I made a conscious effort to include the speaker in the overall judgement here. He should do more, and knows he should do more, but doesn’t, or doesn’t know how.

“Lungs” is inspired by a dish in Southern French cuisine called “Chicken in Half Mourning.” The name comes from the black truffles stuffed under the skin of the chicken, which then looks like traditional mourning wear. The chicken is cooked in the ground for several days, in a bath of milk. After my grandmother died, I came across the crock-pot version of the recipe in one of her kitchen boxes.

Author Bio

Jesse Littlejohn lives in Los Angeles, CA. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Bitter Oleander, Boxcar Poetry Review, Columbia Poetry Review, New American Writing, and elsewhere.