It wasn’t much past four in the afternoon, the sun still well above the quartzite hills, when the Knoche children appeared on Maeve and Leland Mills’ doorstep in tears. Leland was out in the barn, shoveling out after the cows that had spent most of the day in the far pasture. Maeve had just sent David to deal with the chickens. Maeve herself was in the kitchen using her left hand to stir the last of her dried basil into a hot saucepan of mashed potatoes meant for the evening’s supper. It was going slowly, but then what didn’t these days.

Maeve didn’t know how long the children stood on her porch knocking before she heard the soft, persistent staccato over the radio news program. When she opened the door, five pairs of red, wet eyes peered hungrily up at her as though they had been waiting for hours, for days even, stranded, as if there were nothing else in the world but her porch and this door and whatever charitable soul would walk through it and rescue them. They stood in a pack, the oldest, Sam, in front with the other four huddled behind, shoulders pressed into backs, pencil-stub fingers clutching skirts. The youngest wiped her nose on her arm.

She was more than a little surprised to see all of them together without their parents, the girls in their cotton bonnets, the boys buttoned up to the neck. Mr. and Mrs. John Knoche were in their late 30s, just a few years younger than she and Leland, but for the most part the Knoche family kept to their own queer circles. The Amish had a separate dry goods store in town and a separate church. They never came to the village ice cream socials or the outdoor movies the bank sponsored. Still, they always waved hello when they clopped past in their buggy and she and Leland did the same in their pickup. Maeve bought bread from Mrs. Knoche, which she either delivered in person or sent one of the children over with. Never the whole bunch, though. Maeve loved seeing the family’s underwear hanging on the line, crisp and white and monstrous.

Before the boy Sam opened his mouth, she knew in the way mothers do that someone had died.

“Your father?” she asked in lieu of a greeting, her voice tight. The constant throb in her right arm faded.

Two of the children nodded and two of them shook their heads.

“He sent us over here,” Sam said to his feet. He didn’t know what to do with his body. It hung loose about him. The youngest began to cry.

“Pepper! Pepper’s dead!”

“Pepper?” Maeve repeated and she had to pull down her mouth and widen her eyes in an expression of sympathy to hide her laugh of relief. The family dog.

She had never seen children so broken.

“Can Mr. Mills bury him?” asked Karen, who was five and hadn’t quite grown into the hand-me-down tan dress she was wearing.

“Can Leland…what?”

Sam shook free of his siblings and tried to stand a little taller. “Father said your dog died too. He said you buried him in the orchard. We wondered if you could bury Pepper in the orchard too.”

“Oh,” was all Maeve managed. Because what does one say to someone else’s grieving children?

She settled the Knoches in a puddle on the sitting room rug and sat down herself on a nearby ottoman. She folded her hands. After a few moments, that began to hurt so she folded them another way. The children strained their necks to see the house around them. Even in their grief, they couldn’t hide their curiosity. One of them, she was sure, was looking for a television. Well, Maeve thought, he would be disappointed. Money for their mother’s bread had to come from somewhere. None of the Knoche children had ever been invited into the Mills’ electric-wired home. Their parents didn’t approve. But she couldn’t just leave them to wait on the porch, could she? From down the hall, Maeve listened to a toothpaste advertisement jingle on the kitchen radio. She looked around for her knitting, something to occupy her, before she remembered that she had switched from knitting to reading during the evenings, although reading made her fingers twitch and she couldn’t listen to the radio and read a novel at the same time. She liked having the radio on, especially in the isolating Wisconsin winter still many months away. It helped her remember that there was more beyond this valley than other cold valleys.

One of the Knoche children sniffled, which started another one crying afresh. Good, she thought. Leland would never say no to a child in tears. She heard her son, David, come in through the back door and stomp around the mudroom like the fourteen-year-old boy had watched his father do for years.

It had been a month since their golden Labrador Mortimer went missing. Farm dogs didn’t get lost. He had been gone for two days when John Knoche rode past in his buggy on his way back from town and told them about something he’d seen at Greenway Corner where the milk trucks always drove too fast.

“Back legs were flattened, Mrs. Mills, but he looked like he was still breathing.”

She sent David to town for sugar and then over to the Knoches for bread. Leland stood in the doorway until their son was out of sight before taking down the shotgun. He was a farmer. His father was a farmer. She had lost track of how many calves they had loaded up and sent off, but that didn’t make it any easier when they crossed the intersection with County Highway N and slowed down. A milk truck laid on its horn behind them as the tan lump of a body swung into view. No, not a body yet, because as they signaled and pulled over onto what wasn’t really a shoulder so much as an elbow, something separated from the golden mass and their dog Mortimer raised a shaking, matted head.

“Jesus,” Leland said.

There had been hope. In the two minutes it took them to pull out of the drive and speed to Greenway Corner, there had been an unspoken prayer between her and her husband that it wouldn’t be their Mortimer, or else that it wouldn’t be as bad as John Knoche had let on. The vet could fix him up, a few stitches. Worst case, amputate a leg. She’d seen a scrappy mutt jiggling around town on three legs without a care in the world. A car saw them parked and slowed down. Mortimer’s head fell back to the gravel. The hope evaporated.

“Leland,” Maeve said.

Leland sat frozen and unblinking behind the wheel, the bulge of his stomach just slightly visible through his field overalls. He was an average shaped man with the same thick, wide farm hands she had fallen in love with, although his teeth were half of what they had once been, worn down by decades of nightly grinding. The flat stumps lining his open-mouthed smile used to frighten the children at church until he started keeping his lips pinned closed, but Maeve didn’t so much mind. They had been married for sixteen years, twice the amount of time she’d had her tendinitis, and look at how she made do with that.

“Leland.”

He stared out the windshield, his gaze fixed on a smeared trail of blood that began a few feet away. Mortimer’s flank was shuddering in short, distressed breaths. She couldn’t keep watching. One of them needed to—there should always be an end, Maeve thought. Sometimes the body didn’t know when to give up. There’s pain and then there’s what lies beyond it: wild and language-less and dark. Eight years ago when Doctor Fulmer had first looked at her right arm, he’d shaken his head and said, There’s all different kinds of broke.

“Leland,” she said one last time, and when he didn’t move she reached behind his seat, her left fingers curling around the cold barrel.

Her kind of broke still let her set the butt of the shotgun against her shoulder. Her kind of broke still let her pull the trigger. Her kind of broke wouldn’t swell up from the kickback until an hour later. Something else swelled in her too, a power, a satisfaction. It was the most basic need of the soul: the need to effect change. It had been a long time since she’d felt anything close to useful. The shot rocked through her body.

It was going to hurt like hell either way.

Their son, David, chose the orchard as the final resting place. As Leland dug, the unlocked scents of the damp soil rose up from the foot of the tree. A few late blossoms still clung to the ends of its limbs. When the family stopped to take a heavy drink of water, Maeve could hear the buzz of the honeybees. They’d planted this part of the orchard five years ago and were hoping for their first crop of fruit that fall. Everything in farming was such a damn long-term investment.

David slipped his hand into hers while Leland gave a small prayer. The thin, late-pubescent fingers were sticky with sweat. At fourteen, David didn’t let his mother do things like hold his hand any more, but he let her hold it now, and she wanted to hold it forever. She wanted to squeeze it as hard as human skin could take without breaking. She wanted to meld their hands into one. But he was gripping her right hand, her bad one, and all she could do was a light squeeze and then release before her tendons gave out.

“The truck was moving fast. It killed him on the spot,” Leland told their son on the ride back. He waited until dark to remove the shotgun from under the cab seats.

She wasn’t sure how, but after the Knoche children’s visit, word began to spread about Maeve and Leland Mills’ orchard cemetery. She had no idea how many cats and dogs made their home in their farming town of four hundred, but all of them, it seemed, were on their deathbeds. Two weeks after Pepper’s funeral, Maeve’s middle sister knocked on their front picture window, lugging the stiff corpse of a momma cat in a trash bag. Then it was two of the momma’s kittens. After that, the hardware store owner’s mutt and a gray domestic longhair.

August arrived and with it their next charge. The dog belonged to Richie, a broad-shouldered man who had worked with Leland every summer for longer than Maeve and Leland had been together, and it was like losing Mortimer all over again. The bundle swaddled in a crisp, white bed sheet seemed much too small to contain the collie, whom Maeve remembered always herding her and a young David together as she hung the laundry.

Leland told a hunched Richie, “Put her on that bare patch until we get the girls milked. It was her favorite spot, wasn’t it? In the shade.”

She tried not to watch as Richie’s callused hands lowered the bundle to the dirt beside the porch with the same care Leland had shown at his son’s christening. Richie hadn’t brought his collie to work with him since Mortimer had been killed, afraid it would break the dog’s heart. That’s how Richie thought: canine heartbreak. Mortimer certainly had loved his female companion, sometimes in a way that Maeve had to shield David’s eyes from even as she threw things at the pair in the yard and yelled at Mortimer to Get off! For Chrissakes! You never caught the cats copulating in broad daylight.

Maeve held out a jar to Leland, and he unscrewed it with ease before handing it back.

“Can you pack us a lunch basket?” he asked her.

“Don’t tell David what happened,” was all she said.

The August sky was white with humidity that made her joints feel like they were pushing out of her skin. The thermometer read ninety on the north side of the house by the time Leland and Richie returned from the orchard. Back in the hayfield, Richie worked slower than usual, sometimes stopping what he was doing altogether and pulling out a handkerchief to dab first at his beading forehead, then at his eyes. Hot as it was, they were expecting rain tomorrow, and the cut hay needed to be moved into the barn. David went out to join them, but still the hay cart and the tractor only inched along, so after suppertime came and went she hiked out to the barn to take care of the cows for Leland like she’d used to when they were first married. That was before the strain of holding an infant on her hip, of pinching and pulling teats twice a day, of kneading the week’s bread dough, writing crisp figures in the ledgers and learning to type on their Remington Quiet Riter, because it was up to her to keep their books, to keep their house, the chickens, to mend and knit and a million other little finger-tasks that wore the tendons in her arms down. And once the pain got in, it didn’t go away, not unless all the other things did too, and wasn’t that a laugh and a half? On a farm, work didn’t stop until life did, and some days she wasn’t even sure it’d end then. The injury spread, the pain grew, the arm weakened. The work continued.

When the men finally quit well past dark, hay still lay in mounded rows in the field, but Leland didn’t say one hard word about that to Richie. Instead, he asked Maeve to fix up one more parcel of food to send the bachelor home with. Maeve added one of her jars of sweet cherry preserves, even though she’d only gotten a dozen out of the trees that year. Richie forgot he’d already said thank you twice. He said it again and then left.

Leland made a pained sound as he bent over to unlace his work boots. He couldn’t even manage himself a proper supper, just fell asleep in his chair. Maeve covered him with her mother’s pinwheel quilt even though it was still far too warm for blankets. Because that’s what you did with the ones you loved: You swaddled them.

She went out to the pump and drew a bucket of ice-cold water, lugged it up to the porch and plunged her right arm in. It was one of Doctor Fulmer’s many instructions to reduce the daily swelling. The temperature of the water was more than she could stand, and she bit her lip against the sharp pain of it. How many different kinds of pain did a body register, she wondered as she sat hunched over the bucket on the back porch. She focused on the bare patch of dirt beside the steps where Richie had laid his swaddled bundle. Her throat began to ache. She blinked hard twice.

Back when all this had started, when her nerves were still new and the ache fresh, she had cried pathetically often: in her still pristine kitchen at the humiliation of asking her own son to lift the dishes; during her bath as she scrubbed at her scalp. At night she turned in before Leland or David and she would sit at her vanity and stare at her naked body, a body shaped by the same divots and bulges and scars that she’d carried since before the pain crept in. She envied Leland and his worn down teeth, physical evidence of his daily toil and stress. If someone from town saw her request help to the truck with all her grocery sacks or if they overheard her asking her son to chop her some wood for the stove, the neighbor would look at her and think, Her father must have spoiled her something rotten. Or more likely they knew Adam Stanford, bought lumber from him, and would be even more baffled that a daughter of his could display such indolence. The shame pulled at her cheekbones, turned her gaunt. Finally, she thought. Something folks could see.

She hardly ever cried now. Time and resignation had dulled her nerves. She woke up in pain; she went to bed in pain; she cleaned the dishes and pulled the broom, and every day the ache was so boring and unchanging she could die. She had modified her entire life around her impairment. It had become like a second child. Like her David, the swelling grew. It complained. She tended to it and she spoiled it. Prescription slips were filed in her memento box next to photos of David’s first communion. She wanted to explain this to someone, but what would she say? She thought how her sister went on about her unremarkable pair of daughters. No one cared about your children except you.

Maeve swirled her now numb arm around in the bucket of water. A cicada smacked into the overhead bulb spreading its yellow light across the yard and throwing the worn indent of dirt she stared at into desolate shadow. The ache in her throat would not leave. The tears. She closed her eyes. She cried.

The dead pets continued to arrive. Two brown rabbits. A Siamese. The miniature horse took a whole afternoon to bury. It was fifteen minutes out to the orchard on a dry day. Fifteen minutes back. Leland took more and more of his noon meals in a bucket on the edge of a small hole. Hand-hewn grave markers littered the orchard. It was late September by now. David had started high school up in Reedsburg, which meant a half hour wasted on the bus each way when his father needed help with chores. Leland would be damned before he started charging his friends to put their beloved pets to rest, but with all the disruptions he was struggling to keep up.

“Maybe they could help you in the barn for a few hours,” suggested Maeve.

“I’m not asking anyone for payment.”

“It’s not payment. It’s an exchange. Walter is so good with his tractors. Doesn’t that pin on the hitch keep shearing off?”

Leland asked David to pass the gravy and didn’t say please.

“I want to try out for baseball in the spring,” David announced.

Boy, did his father lay into him about that.

One cool evening, Leland was dozing in his chair after a grange hall meeting, and Maeve was trying to force her bored mind through a tattered paperback borrowed from the town library that shared a room with the post office. She didn’t even bother getting to the end of the page before she looked up and announced,

“I need help.”

Leland’s chin was firmly planted on his collarbone. After a pause, he opened his eyes. “A can opened?” His voice was heavy with sleep.

“Real help. The housekeeping. The kitchen. Doctor Fulmer isn’t doing anything.”

“Then stop seeing him.”

“My arm isn’t getting better.”

“You’re keeping up with the chores.”

“That’s why my arm isn’t getting better.”

He sighed and lifted his chin off his chest. When he looked at her, she could see the same exhaustion that she had seen on many of the farmers’ faces who had walked out of that night’s grange meeting. It was the exhaustion of hard labor with low payoff, the exhaustion of fighting with old machines and older buildings, so she was surprised when he hefted himself out of his chair and came to sit by her feet, head laid in her lap like Mortimer used to do. Her stomach did a funny turn and she reached out with her good arm to stroke his head.

“We don’t have the money to hire anyone,” he told her. His eyes were closed again.

“I know,” she said.

“I understand what it feels like. Every night something new hurts.”

“I know,” she said.

It was both the same and not the same at all.

A knock came at the door. The couple looked at each other with an accepted resignation. Word had spread far enough about their orchard cemetery that families from the next town over were coming to their house with deceased pets. Some all the way from Reedsburg. But it was only John Knoche on the porch and his two eldest sons buttoned up in the usual austere, Amish fashion. The thick-bearded man nodded twice and put on a smile, one hand in his pocket, the other clutching a burlap sack.

“Is it that time already?” Maeve asked him, then went to find her shoes.

Twice a year Mr. Knoche and his sons came around to collect the pigeons that roosted in their barn. The practice fascinated Maeve, who never found pigeon eggs or squab to be worth the work of preparation. But free food was free food for those with the fingers dexterous enough to pick those little pieces of meat off of those tiny bones. Leland’s father had sworn by the Knoches’ squab stew, but then Leland’s father had been raising teenagers in the ’30s and no one could be picky then. He had even cut two holes under the eaves of the barn each the circumference of a biscuit in order to encourage the pigeons inside.

“Thank you,” Mr. Knoche said to Maeve, nodding toward Sam, who had bent to pet one of the barn cats. Tonight he wore round, wire-rim glasses that were too big for his small head. “Pepper was the first dog the children remember losing. I did not expect them to take it quite like that.”

“Why do you always hold your arm like that?” Sam asked Maeve.

“Like what?”

The boy demonstrated, pinching his right wrist with his left arm.

“Even when you’re walking, I see you like this.”

“Do I?” She really hadn’t noticed. “Even when I walk?”

He nodded.

So as not to wake the roosting birds, they slid the massive barn doors open just enough to slip inside. Low light seeped in through the opening and through a row of high windows in varying states of disrepair. From his pocket Mr. Knoche withdrew a clunky flashlight, one of the many modern tools Maeve’s neighbors made exceptions to use. She’d heard they had installed indoor plumbing last year too, that the outhouse was now mostly for show and emergencies. He switched on the light. On cue, his two boys scattered, each scampering up a ladder three stories tall, fearless as monkeys. Piled high around them and giving off a smell simultaneously dusty and damp, the loose hay absorbed the sounds of their movement as their small fingers reached silently for rung after rung in the fuzzy half-light.

Mr. Knoche trained his flashlight on the rafters to search out the first roosting pigeon. The beam, when it found one, stunned the bird for a few seconds, which was just enough time for one of the boys to dart across the joists forty feet up and trap the creature in his hands. Humming quietly to calm the startled bird, he then folded the wings in some simple manner that Maeve couldn’t see so that when he let go, the pigeon fell straight down, unable to fly away. She thought of Mortimer frozen in the headlamps of an oncoming milk truck. She heard the thump of his body connecting with the front fender, but it was only the thump of the bird falling onto the hay at their feet. Mr. Knoche collected the confused bird in the burlap sack and then retrained his light on the rafters for the next pigeon.

“Do you also eat grasshoppers?” Maeve asked Mr. Knoche.

A darkness settled on her that night, a darkness that only deepened as the days grew shorter and the first snow came. The delivery of pets dropped off after the ground froze. The crude stone and wood markers poked out of the snow, their tops capped in white like winter mushrooms. The cold kept her inflammation down some, but she had trouble filling the long, sunless nights. For a week she tried keeping a journal, but the grip on her pen hurt worse than the grip on her knitting needles and she couldn’t exactly dictate to Leland or David the sort of things she wanted to write down. She thought often about the ghostly fingers of Mr. Knoche’s son illuminated in the artificial beam of the flashlight as he nimbly folded up a pair of wings, the soft cooing he mimicked to calm the bird before he dropped it, loving and intimate. She thought about the pigeon falling, swaddled in itself, brought down by its own useless appendages. The dazed look in its dark eyes as it bounced onto the hay, the bafflement that said, What? How did I get here?

On New Year’s Eve, David kissed Debbie Jones on the cheek at a party at the American Legion hall. Maeve wasn’t supposed to see, but she did, over the shoulder of Alma Burmester, who was listing her New Year’s resolutions, the first of which was to leave her husband. Leland was drunk on Tom and Jerrys. Maeve’s right arm hung loose at her side. She went home before midnight and wrapped it up in an ACE bandage, listened to the church bells ring from under a pile of quilts that smelled of unbathed bodies. She’d stopped doing the wash as often, and if Leland noticed he hadn’t said anything. She heard David come in and his door click shut. Their wedding clock read two twenty-five when her husband finally came home in a sharp exhalation of rum and January air. He almost missed her lips when he leaned over the bed to kiss her, first of the New Year.

Leland snored when he was drunk. His teeth clattered like two chalkboards rubbing together. Maeve washed in and out of sleep.

It was too dark in the house to read the clock when the knock came, cold and insistent. She nudged Leland with her foot, which only got him snoring again. The knock, two fists now, sounded violent, angry. A robber? Her heart thumped with nerves. Robbers didn’t knock. Had Leland gotten into something at the Legion? She nudged him harder and he still didn’t move, so she wrapped herself in her housecoat, a woolen hat, slippers. She could hear her pulse in her breath as she inhaled and exhaled. Downstairs, she retrieved the shotgun. The wood stove had all but burnt out.

Edwin Jones, of Jones & Jones Furniture and Undertaking, whose daughter Maeve had watched her son kiss not five hours ago, stood on the porch, eyes desperate, arms raised like he was waiting for shackles, ready to knock again.

“I’m sorry, Maeve, I’m sorry. I know the time. Not really, actually. But I couldn’t—I had to—I need to see Leland.”

And now a different kind of panic, a maternal one of shame and guilt. A better mother would have said something at the Legion. A better mother would have hauled her boy home by the ear. But it was only one kiss on the cheek. Her son was too timid to do something foolish. She had taught him that. Don’t try what you can’t accomplish. The things we never mean to pass on to our children.

She invited Edwin inside saying, “I’m the one who should apologize, Edwin. I know David was a little bold, but it being New Year’s.”

“David?”

Only as he bent down did she notice the pine box at Mr. Jones’s feet.

“Debbie…” Maeve began and trailed off.

Edwin Jones was a broad man with overbuilt shoulders and upper arms from digging graves and pounding nails. He was also short, which only accentuated his muscles, but made it difficult for him when a widow with no one else to ask needed one more pallbearer. When the Boerfjin’s youngest came home from France wrapped in a flag, he’d practically had to hold the coffin over his head to keep it level with the other Scandinavian men. Tonight, Edwin Jones had bundled himself in a pair of coats, mittens, scarf and his sheepskin hunting cap. His eyes flitted around the foyer, distracted but sober. Maeve couldn’t remember if she had seen him at the Legion hall that evening.

“Debbie doesn’t know. And I don’t want her to know until morning. She came home from the party so happy. She doesn’t go to many dances.” His voice broke and he swore.

“Edwin,” Maeve’s voice came out quiet, soft. Without thinking she reached out her right hand and touched the sleeve of his jacket. She could still hear the adrenaline in her inhalation. “What’s in the box?”

She already knew. The men always bring their dogs. The women bring their cats.

She tried to dissuade him. She told him Leland wasn’t feeling well and couldn’t get up, that the ground was solid, that they could store the body outside in one of the outbuildings where the coyotes wouldn’t get to it.

“I know that,” Edwin snapped. Fluid dripped from his nose as he moved his head. “Do you know how many full caskets I’m storing right now for the spring thaw? I know how to dig a grave, Maeve.”

The rhyme echoed inside her as Edwin ran a dry, cracked thumb along the edges of the box and whispered to it something she couldn’t hear. Grave Maeve. Grave Maeve. The echo continued as she climbed into Edwin Jones’ truck, unreasonably anxious about driving off into the night, a married man and a married woman.

The setting full moon bouncing off the eight inches of snow was all the light they needed to see the silhouettes of the apple trees. The tops of the quartzite hills that made up this valley wouldn’t begin to lighten for another two hours. The air was a deep cold. Her lashes kept freezing together, making the snow appear to glimmer. She’d brought the shotgun. For coyotes, she said. He had a pickaxe, a snow shovel and a spade. He said the grave had to face the rising sun. Leland had buried his charges every which way. The markers for the full plots were now completely buried, so she’d led the undertaker to the farthest edge of the orchard to be safe. He hefted his tools out of the bed of the truck.

“I’ll take the pickaxe. Can you use the spade?”

She shouldn’t use either, but the pickaxe was definitely the worse of the two. She set the diamond-point spade on the cleared earth and stomped it down. It skittered to the side, jarring her wrist. She stumbled, reset. This time she knocked a hole in the frozen ground the size of a tablespoon. Beside her, Edwin swung the pickaxe close to her leg.

They worked in silence for half an hour until the moon set behind the hills and Maeve couldn’t feel her fingers any more. Edwin stopped to take a drink of something in a thermos that steamed and smelled of whiskey. She turned down his offer to share—alcohol swelled her joints—but when she met his eyes and saw the deep loss that had melted his brown irises to chocolate, she regretted her decision. She wanted him to pass her the thermos again for no other reason than to feel his cold fingers touch hers. She smiled at him. His teeth were crooked but whole, their tops rounded, not deflated and concave like Leland’s. An absurd thought came to her: It was New Year’s morning. A day of fresh starts.

He said, “I heard you shoot the animals the families don’t have the heart to take care of themselves.” She watched him put the thermos away without a second offer. “Would you kill a dying man if he asked you too?” Her eyes shot up to him. He gave a twisted smile too sad for someone who dealt in death. There’s all different kinds of broke. “No, not me.” He hacked at the slight indent they’d made in the ground, stopped to wipe his nose. “Debbie’s grandfather missed the last step off the stoop last week. Fell and broke his, I don’t remember how many things. Ambulance drove him all the way to Madison. My wife’s with him. She called tonight while I was working on the coffin. Pneumonia’s set in. Debbie came home from the Legion so happy. I closed the shop door and sent her straight to bed.”

The eastern edge of the valley had lightened. The cardinals and chickadees had started to stir. Leland wouldn’t wake until midmorning. She had to get back soon to take care of the cows for him. She didn’t want to think about Debbie’s grandfather. Maeve feared falling. The impact on her wrists. Her elbow would break like a toothpick. She didn’t know what she thought about Edwin Jones’ question.

“I can make the tightest coffins in Sauk County. You could raft down the Wisconsin in them. I’ve filled half the cemetery. My father filled the other half. I handle bodies. I sit with widows and children young and grown. When I was ten, Dad pulled me out of school for a week to deal with the aftermath of the Spanish flu.”

Now that she’d stopped moving, the ache was starting to take over her consciousness. She stood, silent. That’s when she heard the whimpers from the beautiful pine box.

“Edwin.” She went to the truck and raised the lid. At first, the container appeared filled only with the shaved red fur of a setter, but then she deciphered a black nose flaring for breath and one eye encrusted in puss wincing at the sudden cold. “Edwin, he’s still alive.”

Edwin didn’t even look up from his work. He had pulled a rabbit-fur scarf over his mouth and nose. Maeve could barely hear him over the swish of his clothes as he brought the axe down. “I’ve never killed anything larger than a mouse.”

She watched the undertaker as he swung again and again at the frozen ground with the ferocity of a man who considered himself a failure.

The privilege of townsfolk, she thought, and whatever New Year’s illusion had attracted her to him disappeared, replaced with the distaste that so often accompanied pity.

Out loud, she said, “It’s different when it’s your own.”

She supposed she meant the dog.

She went and got the shotgun. Edwin Jones held the lid of the pinewood coffin. In the last year, she had watched so many men cry.

She left Edwin picking away at the frozen ground and went to take care of the cows. The sun had broken the crest of the east hills when she returned and still he hadn’t hit the two foot minimum the county ordinance officially required. “Twenty-four inches, Maeve. I can’t live with myself if I do anything less.” She sat in the cab and waited.

As Maeve watched the undertaker bury his dead, she massaged her shaking hand. Hands, she thought. Hands were what differentiated those who were buried on consecrated land from those who got the frozen ground of an orchard. She knew that if she were ever going to heal, she would have to stop working hers the way she did. But to stop using her hands, even for a day, what would that make her? What would she have to relinquish?

Her arm wasn’t so bad, she told herself. She’d handled it this long.

“How much do I owe you?” Edwin asked when it was finally done. Maeve thought of Leland and his own aches and pains that he never said anything about no matter how much they hurt. She thought of how angry he would be with her if she accepted payment from a neighbor. And then she thought of their unwashed quilts, the onionskins stuck to spider webs in the corners of her dirty kitchen. She thought of Leland’s head on her lap. I understand what it feels like.

“How much do you charge for a human burial?” she asked.

He got out his checkbook and blew on his hands until they were warm enough to hold a pen. She noticed a small, dry wart on the undertaker’s thumb as he wrote down the amount.

Back at the house, she took four aspirin on an empty stomach to quell the tremors in her arm and crawled back into bed beside her still sleeping husband. When she woke an hour later, her stomach was killing her. She could hear Leland over the toilet, sick as a dog.

Author Note

In 2015 when I was researching local history around rural Sauk County, WI, for a writing installation for Wormfarm Institute, I stumbled upon an anecdote of a family who inadvertently became the keeper of the town’s pet cemetery. Sadly, the story only stuck in my head, not in my written notes, so I can’t attribute it to the correct family or even town. I mixed this bit of local history with the very personal experience and frustrations brought about by the everyday struggles of tendinitis, a chronic affliction that since I was sixteen has affected my own ability to do dexterous labor including curtailing the amount I am able to write.

Narratives of the rural are almost always ones of physically able bodies (able to cut wood, able to pump water, able to prepare food and clean house and slaughter animals and walk across a furrowed field and be alone). Even in our modern day of automation, these notions of the rural as an able-bodied space persist. It remains a space where we revel in our personal freedoms to exist without oversight or support, be that support federal, social, physical, or pharmaceutical. The rural human is still the self-sustaining human.

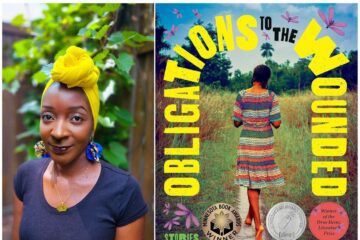

Author Bio

Molly Rideout is a current MFA candidate in Fiction at The Ohio State University, an Antenna::Spillways Resident Artist, and the Executive Director of the artist collaborative Grin City Collective. Her writing has appeared as public art in four Iowa libraries and for the Wormfarm Institute’s Farm/Art DTour. Some of her fiction and essays have appeared in the Wapsipinicon Almanac, Front Porch Journal, Bluestem and the anthology, Prairie Gold: An Anthology of the American Heartland. www.mollyrideout.com